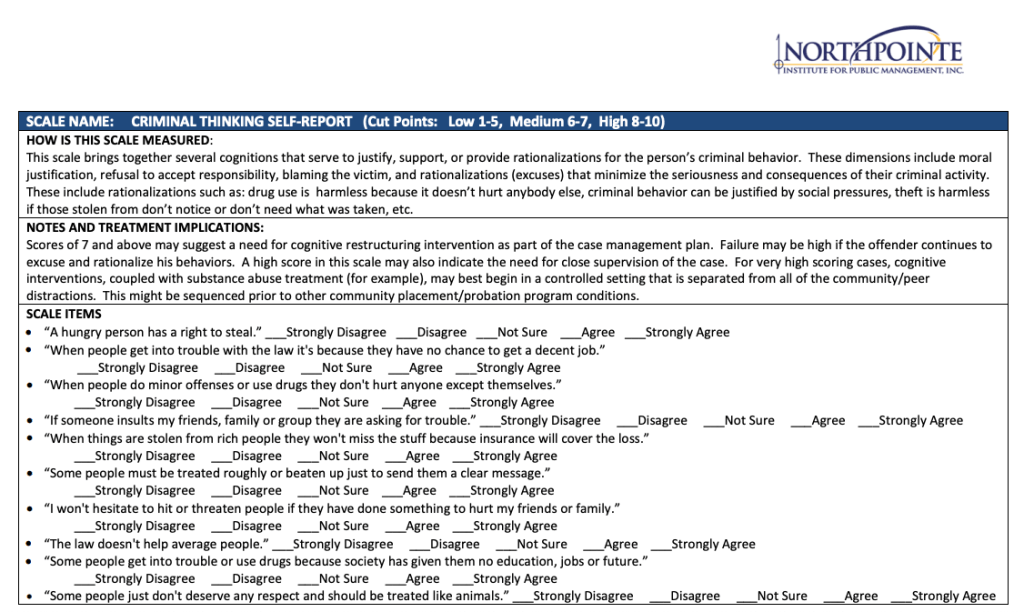

During my childhood the Minnesota Twins played in an arena nobody liked named after a politician of a similar reputation, the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome. The stadium, one of the last indoor multi-use stadiums to be built, forced supporters to spend hours indoors underneath the fluorescent white roof during the precious few months of good weather. This fact, along with the stadium’s other deficiencies and their lack of success following two World Series wins in 1987 and 1991, brought the team nearly to the brink of extinction in 2001, the same year the hero of those championship teams, Kirby Pucket, was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

All this made them the consummate underdogs, especially compared to their playoff nemesis the Yankees. George Steinbrenner seemed to be motivated each year to buy the best team he could. The Twins’ owner Carl Pohlad seemed to have the opposite desire in spite of being worth a couple more billion than his New York counterpart. In 2001 the Yankees spent $109,791,89 on team payroll, over four times the Twins’ total. That year the Twins payroll was dead last in baseball at $24,350,000, almost ten million dollars less than the next lowest team, the Oakland A’s.

Oakland, specifically the teams of this era, would become famous underdogs via the work of its general manager Billy Beane. At the turn of the millennium, he led the team to multiple 100+ win seasons on a fraction of the payroll that teams like the Yankees did to accomplish the same thing. This process, described in Michael Lewis’ book Moneyball and later in a film of the same name, was presented as a departure from the typical methods of player development and deployment. Because of their budget, the team was forced to find undervalued players to fill specific roles that, when placed together, seemed able to compete with the Yankees at a fraction of the payroll.

It’s an appealing story, especially for a fan of another small market team. But the fact that the very team chronicled in the book lost to my Twins that year, whose team lacked such a novel philosophy, could suggest it’s perhaps not as unique or effective as its outsized reputation.

Show me the Moneyball

Before he was general manager of the Oakland Athletics, Billy Beane was himself a consensus top prospect. In his book, Lewis describes how Beane and outfielder Darryl Strawberry competed for the attention of top scouts for the New York Mets, who had the first pick in the 1980 draft. Eventually, Strawberry was taken first overall by the Mets, who then used one of their later picks in the first round on Beane at 23rd. Beane’s major league career would be over before the decade was out. Strawberry, by contrast, played in the majors for 16 years until 1999, just three years before the action of Moneyball takes place and long after Beane had transitioned from the dugout to the front office.

This experience, especially the high praise lavished on him by scouts contrasted with his middling performance in the majors, left Beane with a skepticism of the traditional methods of prospect evaluation. For as much as this would define Beane’s approach to building his teams, it also reveals what would become a common trope for Lewis’ work: a fascination with those who appear to buck conventional wisdom, seeing a unique opportunity where others have not even thought to look. Like the financial titans he would skewer in The Big Short a few years later, the old fashioned world of the scouts Lewis portrays in his book seems parochial and out of touch, almost waiting to be shown up by someone with a fresh perspective and the commitment to their vision.

While this does make for a useful narrative arc for a book, I found myself wondering whether this was a useful rubric for understanding baseball, which more so than most sports is about big sample sizes and regression to the mean, especially over the course of a season or career. This statistical note is important to point out here because of what would become the executive summary of the Moneyball approach once it became the kind of bestseller that executives have to at least pretend to have read: Beane and the A’s pioneered a new way of running a baseball team by relying on statistics, rather than old fashioned gut feeling, to assess players better and succeed with a lower payroll.

For Lewis, Beane’s approach was the culmination of what Bill James had been begging teams to do for years. James sought to apply rigorous analysis to the game of baseball. This came to be known as “Sabermetrics”, so named for the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR). From humble origins, James created an audience for independent baseball writing and analysis that came not from watching a single team through the course of a season but by analyzing the entire league or in some cases the entire statistical record of baseball. He relished in challenging the consensus, from what makes players good to what makes a good team great.

Take the traditional focus on batting average as the indicator of a player’s offensive capabilities. For James, tallying up just the percentage missed two key facts:

- Players can also get on base (and therefore score a run) via a walk, but these are not counted towards a player’s batting average

- Extra base hits (doubles, triples, home runs) are far more valuable than mere singles, but they all count the same in a player’s batting average.

James, and Beane’s team at the Oakland A’s, were far more interested in an offensive player’s on-base percentage (OBP) and slugging percentage (SLG) than the more traditional batting average. These could be added together to calculate a new number, On Base plus Slugging or OPS, that would not only factor in how often the player reached on a walk but also capture how often they hit for extra bases.

This is on the simpler end of statistical analysis in baseball, especially nowadays, in part because the game itself lends itself so well to statistical analysis. It comprises a large number of discrete events that all begin and end from the same state: a pitcher throws the ball to a hitter. Only the team hitting can score runs and only the team in the field can record outs. There’s no clock, or there wasn’t then. Only the act of recording the 27th out or, more rarely, scoring the winning run as the home team, can bring the game to an end. Over the years many improbable things have happened that buck the expected outcome, but we only know how improbable they are precisely because there is so much data that demonstrates their improbability.

While Sabermetrics was controversial for some, it’s become an inescapable part of the modern game. Contact by a hitter can be measured in terms of its exit velocity and angle off the bat. Individual pitches can be assessed on how often it induces swings and misses or weak contact. A player’s season or career can be assessed in terms of how they performed in a particular situation but also how much they contributed to a team’s winning relative to the average available player, usually summarized as Wins Above Replacement (WAR). When Bill James started he had to manually compile the statistics he was interested in because they were often unavailable to the public and in some cases not even tracked by major league teams. Now this kind of information is available to anyone on a site run by Major League Baseball.

While statistics were one half of the Moneyball story, the other had to do with the labor market in baseball itself. If most teams were looking for players with high batting averages, they would be likely to undervalue a player with a low batting average who nevertheless managed to get on base often. For Beane and his front office team, who included other devotees of Bill James who had backgrounds in finance instead of on the field, this was an opportunity.

And this is precisely what they did, except the best exemplars of their method came not from their offense but for pitching. The three best starting pitchers for the Athletics in 2002 were Barry Zito, Tim Hudson, and Mark Mulder. They had two important things in common: all were relatively early in their career and all made less than a million dollars in 2002, in part because they were not eligible for free agency, which meant they couldn’t negotiate better contracts with other teams. That year each looked poised to become dominant starting pitchers, and for now the Athletics had them at severely below-market rate.

The performances of Zito, Mulder, Hudson for Oakland in 2002 at such low salary gave Beane the budgetary flexibility to replace the most talented players they had lost in free agency. The two highest paid players on their roster that season, David Justice and Jermaine Dye, were not uncut gems discovered by the team but established players. Justice was a good hitter but past his prime, who Oakland wanted because of his approach at the plate. Dye, on the other hand, was entering the prime of his career and would have led the team in OPS the year before had it not been for Jason Giambi, who had been granted free agency and signed with the Yankees after almost ten years in the Athletics organization. It just so happens that the combined salaries of Dye and Justice match almost exactly the going rate for top notch starting pitching that same year.

In 2002 Pedro Martinez led the entire league in ERA+, meaning he had the best ERA relative to the entire league average. He was just about to enter his highest-earning years as a player, earning $14 million in the 2002 season. Randy Johnson came after him, also at or around the peak of his earnings. If you watch highlights of either of these pitchers at the peak of their power, it would be easy to argue they are still underpaid. Even though neither of them competed in the World Series that year, both were among the leaders of their respective rosters in WAR, with Johnson followed by two more pitchers Curt Schilling and Byung-Hyun Kim.

That is how important good pitching is to success in baseball. Good relief pitchers protect even slim leads and convert them to wins. Good starters can set the team up to win lots of games in the regular season and form the bedrock of a successful postseason run. Pitching on short rest, it’s possible to only use your best pitchers in the playoffs, which is exactly what the Twins did when they played in the 2002 American League Division Series. Because Zito pitched in the last game of the regular season, he was unavailable for the first game of the series, which the Twins won behind an excellent bullpen showing by Johan Santana, J.C. Romero, and Eddie Guardado. Good pitchers at below the market rate is exactly what the 2002 Athletics had done and that was key to them tying the Yankees for 103 wins in the regular season. That is why it’s all the more remarkable that the team to beat them in the playoffs was the Minnesota Twins.

I would argue it was the moves Beane made to secure this trifecta of pitchers that had the biggest impact on their success. This is borne out by the WAR statistic as well, as they finished first, second, and fourth on the team in this category. The player that splits them in this stat, Miguel Tejada, features in the book as the antithesis of the kind of player Beane is after. That Lewis spends almost no time at all on these pitchers compared to the ups and downs of signing Scott Hatterberg or the drafting of Nick Swisher in the draft that year shows I think another blind spot of his when it comes to understanding baseball. To fill this spot in, we have to go back to the basics of the baseball labor market, which have been distorted in important ways since the earliest days of the game.

The Reserve Clause

From the very beginning of organized professional baseball, team owners wanted the best players as their exclusive employees for the lowest possible salary for the greatest number of seasons possible. Initially this happened through a reserve clause in the player’s contract that prevented him from negotiating new contracts with another team who might also want his services. Buttressing this legalese was an even more sacred gentleman’s agreement between the owners to not poach players from other teams. In 1890 the conflict came to ahead in the form of a player-owned and led league called, appropriately, the Player’s League, which competed for a single season before folding, taking with it the best chance to do away with the reserve clause until a few decades into the next century. (For a detailed history of the Player’s League, see this excellent essay).

Even when the highest salaries were measured in thousands and not millions, the basic rules of the labor market for baseball players functioned this way. As the years went on, the dynamic swung even more in the owner’s favor through open collusion to limit the number of teams and thus reduce the available roster spots in the major leagues, including specific protection from antitrust laws granted to them by a 1922 Supreme Court decision. With the advent of farm systems the notion of team control became even stronger, as player’s signed minor league contracts in the hopes of working their way up to the major league team, but only one team. Unless they were traded, in which case they’d move from Cedar Rapids to Waterloo and back again for a few thousand bucks whenever the manager wanted to trade them. This is what the A’s did with Jason Giambi and what the Twins did with one of the key players in their 2002 campaign, as we will see later.

I have simply had my heart broken too many times by the team to say anything positive about the Yankees, but when looked at in this light is there really something all that nefarious about Steinbrenner’s approach? Is it really so awful to simply outbid other teams by paying a player what they would ask for in exchange for instead of what the front office would prefer? Only very rich people can own a major league baseball team. And yet if a player leaves a beloved fanbase in exchange for more pay in a bigger market, he is often reviled as greedy when that anger might be better directed at the home team’s front office for not working harder to keep them.

In 2000 a group convened by then-commissioner Bud Selig published its findings under the title The Report of the Independent Members of the Commissioner’s Blue Ribbon Panel on Baseball Economics. They had been charged by the commissioner to investigate whether disparities in revenue and therefore payroll were destroying the competitive balance within Major League Baseball. The group consisted of conservative commentator George Will, former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, Yale economist Richard Levin, and longtime Democratic Party Senator George Mitchell, who in just a little over a year would be appointed to lead the investigation into the 9/11 terrorist attacks. They concluded that indeed the economic divide between baseball franchises was perhaps the only one that demanded redistribution from the richer to the poorer.

Their recommendations included instituting a luxury tax on payrolls above a certain threshold and a draft where poor-performing teams could draft players from the organizations of more successful teams. Some of these were implemented in some form and some were not, but what I found most interesting is the assumption they state before plunging into their analysis of the game: “This report assumes that, year in and year out, player salaries and other costs of operating an MLB franchise ultimately will be borne by the fans of the game”. This means, they declare, that the interests of the fans are paramount, but it also means the capital of the owners must be preserved.

Lewis devotes a section of Moneyball to reveling in the living rebuke of complaints about competitive balance that is Billy Beane’s Oakland Athletics. Year after year they seem to compete or outcompete teams with much higher payrolls through their novel method and savvy approach to team and player development. And he is, as is often the case in his books, half-right: many teams who found themselves uncompetitive during this era had spent a lot of money on players who did not perform, or perhaps had too little revenue to justify big spending but no plan to win otherwise. But Lewis presents the unconventional approach of the A’s as perhaps the only solution to teams in their situation when in fact it is one of many options. Also, we now know from hindsight that it was not effective at winning the team a World Series or even an American League championship.

That Lewis went on to become a chronicler of America’s various financial crises from The Big Short to his forthcoming book about the collapse of crypto exchange FTX makes it all the better to examine the underlying financial and economic assumptions in Moneyball: that many professional players are overvalued relative to their contributions, that teams waste money by paying them high salaries when they could get by with less, and that small market teams were simply foolish for trying to develop players that could compete with better teams. Lewis was fascinated by Beane’s approach because it fit the same mold of unlikely heroes overcoming against all odds that he would go on to shoehorn into the history of the 2008 financial collapse with the Big Short.

This narrative arc is as pat as it is appealing, which is why as a used book store employee I have to assume Lewis has sold more nonfiction books than just about anybody. And it’s not that he’s wrong to say that Beane’s approach to running the team, which covered not just scouting and development but in-game decisions, wasn’t interesting or a departure from the norm or not worth writing about. But when you’re always interested in the guy who thinks he’s solved something lots of other people are also looking at too, it’s a recipe for tunnel vision. Which brings us to the team that would end the Moneyball season: the Minnesota Twins.

Scroogeball

In 2002 the Minnesota Twins had the lowest payroll in baseball, a few million dollars behind the Oakland Athletics. While Beane and the Athletics front office was putting together their unorthodox 2002 draft list, the biggest question both within and without the organization was over the very existence of the team.

In November 2001 the owners of Major League Baseball voted to eliminate two teams from the league. Though the teams were not named, it was widely speculated that the teams on the chopping block were the Twins and Montreal Expos. If I close my eyes I can still summon the hatred I felt as a ten year old for the men in suits, including Selig, who threatened to dismantle the Twins. When I visited the Hall of Fame with my dad last year to watch two more Twins be inducted into the Hall of Fame I, a fully grown adult, instinctively flipped off Selig’s bronze plaque before even realizing I was surrounded by kids.

The contraction was thought to be a way to eliminate the problem of too many non competitive teams. It was also speculated that the move was an attempt to gain leverage in the upcoming negotiations with the Player’s Association, with the vote coming mere hours before the existing agreement was set to expire.

Twins’ owner Carl Pohlad was eager to be bought out by his fellow owners after years of trying to get public funding for a new stadium to replace the dilapidated Metrodome, which even at its construction was a poor fit for baseball having been designed primarily for football. All through the winter of 2001 the league’s lawyers fought to overturn an injunction preventing the team from being disbanded issued by Hennepin County District Judge Harry Crump. For all its myriad faults, it was the Metrodome that may have saved the franchise. Crump ruled that the Twins must remain extant at least until their lease with the stadium expired in 2002.

The injunction halted negotiations over contraction plans, and eventually it was abandoned. This meant that the Twins would indeed play the 2002 season, but under a shroud of uncertainty. Just like the A’s were looking to avoid investing in the long term payouts of high school prospects in their draft picks, the owner of the Twins was hardly likely to invest heavily in a team he had just tried unsuccessfully to disband.

The three highest paid players on the 2002 Minnesota Twins were pitchers: starters Brad Radke, Rick Reed, and Eric Milton. 2002 was also the first year Johan Santana would see consistent time as a starting pitcher and he would lead the team in ERA+ and Fielding-independent Pitching (FIP), which tries to measure the pitcher’s performance independent of any impact that the players behind them have in turning hit balls into outs. Because of the rules of team control he was unable to leave the franchise and negotiate a better deal elsewhere, earning just over $200,000 that year. Though their payroll was low, the bulk of it lay in their starting rotation. This gave them the depth to win the division and ultimately a five game playoff series against the Athletics, though like Oakland they received a boost from young pitchers still under team control.

The highest paid position player for the Twins was All Star centerfielder Torii Hunter, a top prospect drafted almost ten years earlier. He was arguably the best defensive centerfielder in the league and would become one of the primary run producers along with fellow outfielder Jacque Jones and David Ortiz, one of the few players to be inducted into the Hall of Fame as a designated hitter for his performance with the Boston Red Sox.

Hunter is an interesting figure in this story because he embodies two things that would run counter to the Moneyball thesis. First, he was drafted as a top prospect right out of high school. This is the exact kind of thing Beane is celebrated for not doing in Moneyball, as he considers them both too risky and too far removed from contributing to the major league team. Lewis recounts Beane’s glee upon learning that so many other teams are fighting for high school outfielder Denard Span that he will be able to draft his preferred choice, infielder Nick Swisher, after all. “Eight of the first nine teams select high schoolers,” Lewis writes. “The worst teams in baseball, the teams that can least afford for their draft to go wrong, have walked into the casino, ignored the odds, and made straight for the craps table” (p.112). In Lewis’ treatment, picking players with greater upside but more risk and a delayed payoff is nonsensical. But if you look at the entire draft that year, you see it includes both players who never made it to the major leagues alongside Prince Fielder and future Hall of Fame pitcher Zack Greinke.

Secondly, Hunter’s best asset as a player was his superior fielding ability, which has always presented challenges for statistical analysis. Consider two plays: a flyout hit to almost exactly where the outfielder was already positioned and a leaping catch against the wall ,robbing the batter of a home run. Anyone who has watched a game knows that these two plays are vastly different, both in the skills required and the effect on the game’s outcome. But as far as the scorecard, and therefore the stats are concerned, these are the same. For many years the only notable fielding stat was errors, which measure what a player failed to do. Think of how confusing it would be if hitters were measured by the percentage of at bats they didn’t get a hit or pitchers by the amount of batters they didn’t strike out. An outfielder with many more errors than average was probably a poor fielder, but there was no way to identify great fielders statistically. But this was Hunter’s greatest and most consistent attribute as a player, both to the team in terms of wins and to fans in terms of entertainment (consult this or any other highlight reel if you don’t believe me).

This is what makes the Moneyball narrative a bit grating, especially with the benefit of hindsight. Lewis simply cannot help but valorize people who zig when others zag, despite the fact that sometimes it just makes sense to zag with everyone else. Teams commit to the long term payoff of a younger prospect instead of the more reliable performance of college players not because they are unaware of the risk but because of it. The Twins drafted and kept Hunter in the organization through his early, undervalued years and gave him his first big contracts as an established major leaguer. Many things could have gone wrong in that process, of course, but through Hunter’s own hard work and the patience of the front office, they didn’t, which meant Hunter was there to help the Twins beat the A’s in the first round of the playoffs.

Many of the high school players drafted ahead of the A’s picks in Moneyball never reached the major leagues, but if you look up many of the players that Beane gushes over in Moneyball, most of them never made it there either. And the fact that the A’s impressive regular season win totals during the years leading up to and following the seasons chronicled in Moneyball never translated to success in the playoffs, including their 2002 loss to the Twins, suggests that Beane did not unlock a secret recipe for success as Lewis portrays it.

If anyone deserved to have a bestseller made about an improbable team written about them, it should have been the Twins. Their defeat of the A’s is to this day their most recent playoff series win. Though they won another playoff game a couple years later, they currently have the longest active playoff losing streak in baseball. But the secret wasn’t a unique player analysis model. It was one of the oldest models in the book: labor arbitrage.

Conclusion

The 2002 MLB season is memorable to me personally because it very well might have been the last season of the Twins’ existence, but its inclusion in Moneyball has made even casual fans or people shopping at bookstores aware of it as well. And the fact that the team he praised for its low-budget success managed to lose to the only team with an even lower payroll is a fitting coda to an early version of Lewis’ renegade upstart stories.

That the A’s did not win a World Series using Beane’s method does not mean it wasn’t notable or interesting. That they lost to the Twins doesn’t mean Minnesota’s longtime General Manager Terry Ryan had the real secret to winning on a low budget either. Ryan made some successful trades for players along standard baseball lines, namely trading older players to teams who needed immediate contributions for prospects who would benefit losing teams in the long run. Cristian Guzman and Eric Milton were key members of the 2002 team acquired through a trade with the Yankees for Chuck Knoblauch a few years earlier. Ryan traded pitching prospect Jared Camp, who never made it to the majors, for Johan Santana in 1999. A.J. Pierzynski was traded to the Giants following the 2003 season for future shutdown closer Joe Nathan and ace starting pitcher Francisco Liriano. Those were great trades, but there were ones that did not work out so well too. That’s the nature of the game. They were not saved by the eschewing of old dogmas or the embrace of a new system, even though that inarguably makes for a better book.

Ryan also relied on the scouting of Mike Radcliff, who passed away just last year and was the paradigmatic old school scout of the kind Lewis spends the early chapters of Moneyball skewering. In this year’s draft the Twins lucked into the fifth pick and selected high schooler Walker Jenkins, who was the subject of one of Radcliff’s last scouting reports (he gave him the highest possible marks) and is currently one of the highest rated prospects in baseball. Radcliffe found many great players for the Twins and likely recommended some that didn’t pan out. That’s the nature of scouting. If I had to guess, he likely relied on a mix of statistical analysis and experience, which in the end is all anybody making these decisions has to go on in the moment.

Look through the 2002 statistics and you will be hard pressed to find the Twins at the head of any category, either individually or as a team. For that matter, you would have hard time finding the Athletics at the top of many categories either, despite their notable obsession with stats like on base percentage. The fun of examining these things in hindsight is that you know for certain what happened, so all that’s left is to test different theories as to why.

Did the Angels win the World Series because they struck out the least of any team? Probably not considering the Kansas City Royals had the next fewest strikeouts and they did not make the playoffs.

Did the Giants reach the World Series because they had Barry Bonds, who led the league in most offensive categories as well as overall WAR? That’s more persuasive considering he is one of the best hitters over the last few decades, performance enhancements notwithstanding, but comparing the individual stat leaders to the outcome of their team’s season introduces plenty of noise along with whatever signal is being transmitted.

Teams have won lots of games with low payrolls and teams have emptied their pockets completely and failed to make it to the postseason. This year, Oakland has the lowest payroll in baseball to go with one of the worst records, with many speculating they will be moved to Las Vegas. The fans have had to organize months-long protests against ownership to keep the team where it’s been for decades. The teams with the second and fourth lowest payrolls, Baltimore and Tampa Bay, have been competing for the best record in the most competitive division for much of the season. On the other end, both New York teams had the two highest payrolls and neither are likely to make the playoffs, along with fellow big spenders the Padres and Angels.

Baseball, like many things in life, would be easier if there was one weird trick to accomplishing what you want. Those running teams have not stopped looking for a competitive edge, but their options are constrained by the reality facing each team, whether that be the need to trade the few good players on your crappy team for future value or the short term payoff of filling a roster hole in exchange for watching a prospect become great for another team. If the Moneyball system really was the silver bullet it’s made out to be, then every team would be doing it, but they aren’t for one simple reason: you still have to play the game to find out who wins.